Hormones - Feminising

Hormonal gender affirmation is an important part of many trans and gender diverse people’s lives. Feminising hormones are typically used by trans people who were presumed male at birth (PMAB), including women and non-binary people.

There are several hormones that come under the category of ‘feminising hormones’. The physical and psychological effects that feminising hormones have on the body depend on the type prescribed as well as personal factors including your age, body, hormonal history, any existing health issues, and what you want to take.

TransHub uses the terms masculinising and feminising hormones to describe the effects that hormonal affirmation has on bodies, but not to describe the genders of the people using them. You can be a woman who uses feminising hormones, you can also be non-binary and use feminising hormones as well, there is no one correct form of hormonal therapy. Being on feminising hormones isn’t the thing that makes you, you. Who you are is always valid.

Information and resources to assist clinicians learn more about feminising hormones can be found here.

Types of feminising hormones

There are two main forms of feminising hormones: estrogen and progesterone, as well as androgen (testosterone) blockers called anti-androgens.

Estrogen

Illustration by Samuel Luke Art

Estrogen is the primary feminising hormone used by trans women and non-binary people (PMAB). In Australia, estradiol (E2) levels are monitored, rather than estrone (E1). Estrogen affects many parts of the body, including fat cells, bones, some muscles, skin, and hair.

The Australian Position Statement on the Hormonal Management of Adult Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals 1, published in the Medical Journal of Australia on 5 August 2019, states that “treatment should be adjusted based on clinical response”. This acknowledges that the clinical management of gender affirming hormones should be individualised, and requires partnership between a treating physician and the trans patient.

This means prescribing estrogen based on how you respond to treatment and alongside risk factors, rather than based solely on specifically targeted levels.

Notwithstanding this, the Position Statement 1 does recommend targeting estradiol levels of 250–600 pmol/L and total testosterone levels < 2 nmol/L (ie, to the pre-menopausal cis female reference range).

This is controversial across both the trans and medical communities though as these targeted levels are based on recommendations and evidence that are considered Grade 2B i.e weak recommendations on moderate evidence. As described by the Position Statement, “this approach classifies recommendations as strong (1) or weak (2) and evidence quality as high (A), moderate (B), low (C) or very low (D).”

Estrogen can also affect mood, with low estrogen levels linked to reduced mood. Talk with your doctor about the outcomes you want, and you can work with them to find the dose that feels right for you. If you’re on a particular dose and it doesn’t feel like it’s working or feeling right, you can ask to change it up or try something new too - no one is in your body but you so it’s important to listen to what your body is telling you. Some people will take a higher dose of estrogen, and others a lower dose, or somewhere between the two.

Some research suggests an increased risk of blood clots and other health issues as a result of taking estrogen. There is limited research including trans women, which shows estrogen hormonal therapy (especially oral estrogen) can increase your cardiovascular risk to that of cis women1.

It is recommended that levels are monitored at baseline, every 3-4 months for the first year, and then annually once your estradiol and testosterone levels are adequate and stable. This includes a full blood count, renal and liver function, blood pressure and lipids, and blood glucose for patients with risk factors.

The Position Statement has been endorsed by AusPATH, the Endocrine Society of Australia (ESA) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP).

Illustration by Samuel Luke Art

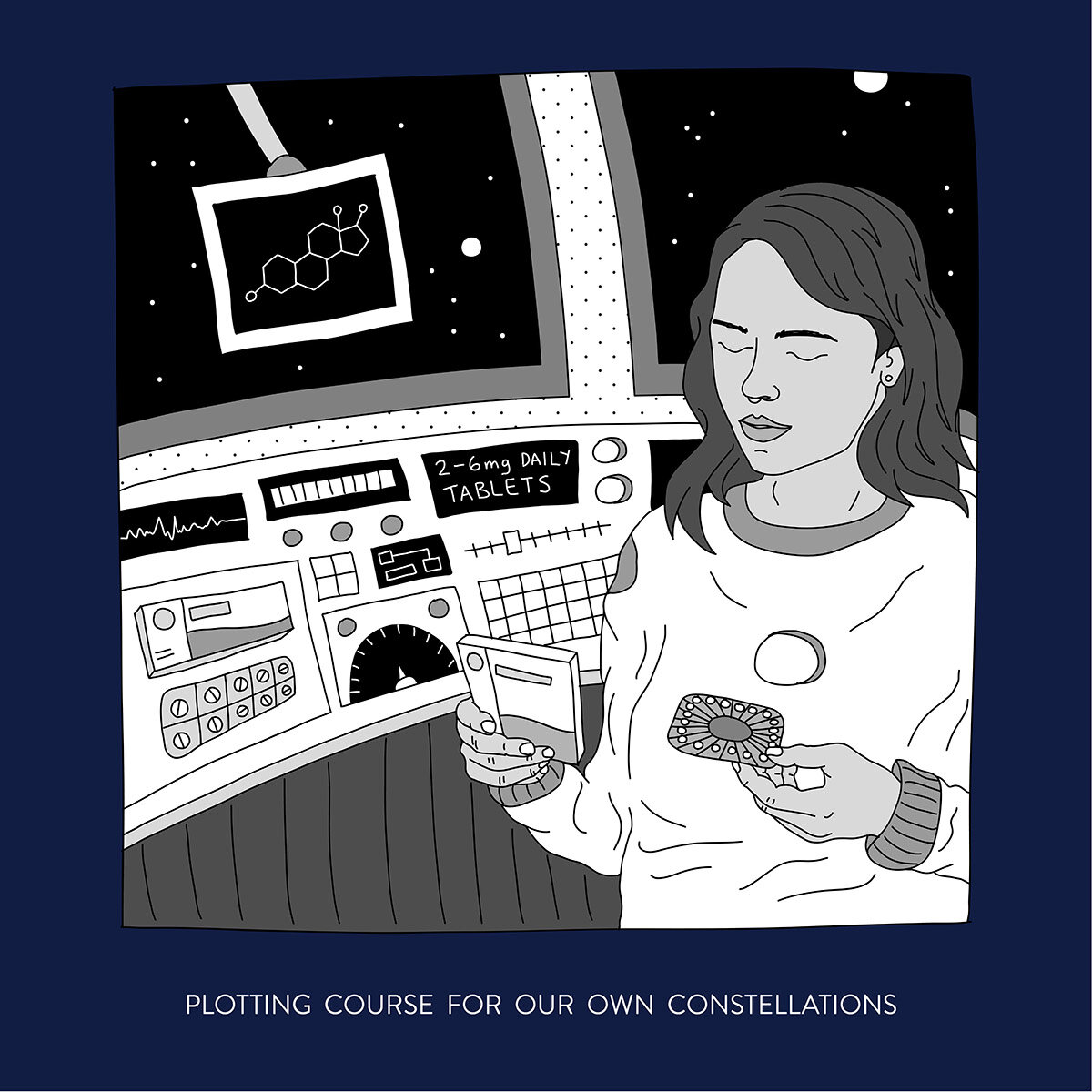

Estrogen regimens

Estrogen is usually taken in one of the following forms:

Pills - Taken either orally, or sublingually (dissolves beneath the tongue or between the cheek and gums). Doses usually start with 2-6mg estradiol valerate tablets daily, increasing to up to 8mg as needed.

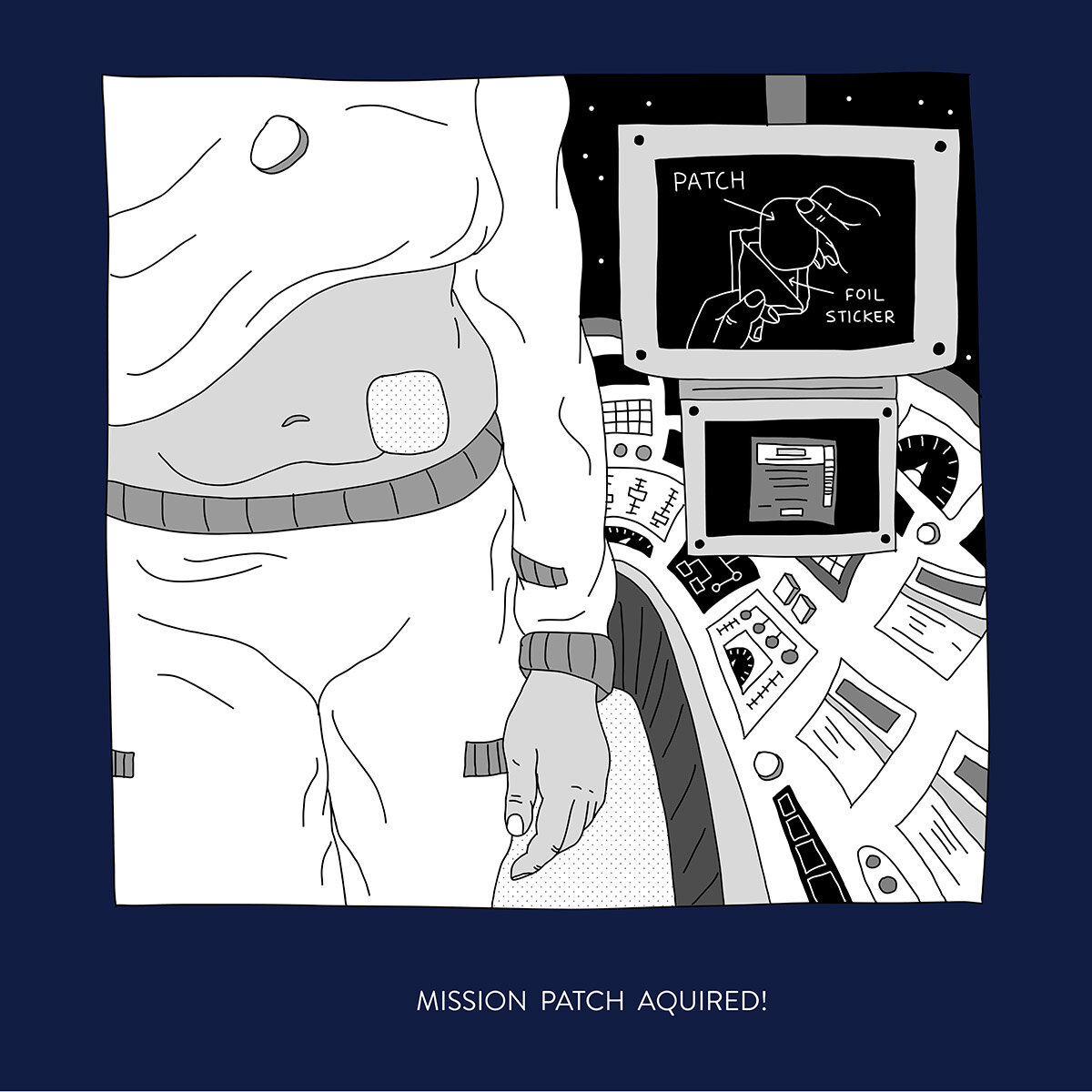

Patches - Placed onto the surface of the skin. Doses are usually between 100–150 μg/24 hours changed twice weekly

Gels - Estrogen gels are less common in Australia than other methods.

Injections - Injectable estrogen is less common in Australia than other methods.

Implants - Available through particular doctors. Subdermal estradiol implants are fused crystalline hormone pellets prescribed by a doctor that you will need to have manufactured from a compounding chemist. Estradiol implants can vary from 50-200 mg pellets, with between 50-100 mg generally considered a preferred dose. Pellets are replaced every 6-24 months, depending on how you respond. The insertion procedure takes approximately 15 minutes.

Typical changes from estrogen (varies from person to person)

| Average timeline | Effect of Oestrogen |

|---|---|

| 1–3 months after starting oestrogen |

|

| Gradual changes (maximum change after 1–2 years on oestrogen) |

|

Androgen blockers / anti-androgens

The role of androgen blockers (or anti-androgens) is to suppress production of testosterone and/or block its effects on the body.

These include:

Cyproterone acetate - the most commonly prescribed form of androgen blocker in Australia. ‘Cypro’ is not commonly prescribed in the U.S. due to FDA restrictions, but it is a safe and effective form of androgen blocker.

Spironolactone - the second most commonly prescribed form of androgen blocker in Australia. ‘Spiro’ is a potassium sparing diuretic, which can result in needing to go to the bathroom more than usual.

Finasteride / Duasteride - far less commonly used. They work by blocking conversions of testosterone to the androgen dihydrotestosterone, and are sometimes prescribed to men (trans and cis) for male-pattern baldness.

Bicalutamide - an emerging non-steroidal anti-androgen that works by blocking the androgen receptor. This is not PBS-listed.

Typical changes from Anti-Androgens (varies from person to person)

| Average timeline | Effect of Anti-Androgens |

|---|---|

| 1–3 months after starting anti-androgens |

|

| Gradual changes (maximum change after 1–2 years on oestrogen) |

|

Progesterone

While there is limited evidence to support the use of exogenous progestin or progesterone as part of a feminising hormone regimen, some trans women anecdotally report progestogens being an effective and important part of their hormonal care, particularly bioidentical progesterone. Studies on progesterone use in trans women have historically assessed the use of medroxyprogesterone, rather than bioidentical progesterone.

Jerilynn C Prior2 makes the case for using bioidentical progesterone to mirror the hormonal health and cycle of people presumed female at birth, due to it being seen as identical to naturally occurring progesterone (ie. progesterone produced in the body) by the body.

Progestogen is usually taken in one of two forms:

Micronised progesterone capsules - dosage recommendations of oral micronised progesterone can be 100-200 mg daily. The Therapeutic Goods of Australia approved Prometrium, or a compounded version, is typically prescribed. Pharmacies charge different prices for oral micronised progesterone, so it’s worth calling around to find the best price.

Medroxyprogesterone tablets - a progestin, which is different to progesterone. Progestins are synthetic, and cannot be detected by a blood test.

Cyproterone acetate is used as an antiandrogen blocker, it is also a progestin.

Some people prefer to work with their doctors to monitor their progesterone levels. The evidence for this is minimal, but if this is important for you, talk to your doctor.

Studies on progesterone use in trans women have historically assessed the use of medroxyprogesterone, rather than bioidentical progesterone.

Side effects of medroxyprogesterone can include anxiety, and some community members report other negative psychological effects, which can be severe so it is important to monitor your mental health and discuss any changes with your doctor. Additional research has concluded3 synthetic progestins may be further associated with increased venous thromboembolism risk, risk factors that don’t appear significant with bioidentical progesterone.

Medical professionals are still arguing about the importance of progestogen in hormonal therapy, but progestogens can be an important, and to some people essential, part of hormonal affirmation, and you are well within your right to request it. Anecdotally, trans women and non-binary people that use progestogens tend to report finding either feminising benefit and continuing to take it, or feeling symptoms such as low mood and fatigue alongside no marked feminising benefit, and so stop taking it.

Testosterone

Although sometimes controversial, maintaining testosterone levels to a cisgender female range (between 0.3 nmol/L - 0.7 nmol/L) can be really important for good health, if only to reduce the potential of developing osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. This is particularly important for trans women and non-binary people presumed male at birth who have had an orchiectomy as the remaining adrenal testosterone may not be a sufficient protective factor. Some people prefer to look out for things like fatigue or decreased libido rather than aim for a particular range.

Prescribing guidelines1 state that people “who wish to maintain erectile function may desire higher levels of testosterone; however, this will offset feminising effects”.

Effects on primary and secondary sex characteristics

Hey! While talking about bodies in this section, we use medical terms like ‘penis’ and ‘testes’ to describe our bits. This is just so you know what we're talking about, as our communities often use similar words for quite different body parts - particularly our genitals.

When talking about yourself, or being referred to by others, we encourage you to use and request the language you feel most comfortable with instead! For more information about affirming language for our bodies and bits, click here.

Fat distribution

One of the main effects of feminising hormones is the distribution of fat to different parts of the body. This includes but is not limited to breast development, increased hip and thigh size, a slight change in the shape of the face, and more fat around your pubic bone.

Breast growth

Breast growth is a common effect of feminising hormones, starting with tenderness and swelling, and growing larger over 3+ years.

Genitals

Shorter term, people on feminising hormones may have less erections, including less or no spontaneous erections. Longer term, the size of the penis and testes will decrease.

Skin

Many people report that feminising hormones dramatically soften their skin. They may also have an effect on sweat, including how much sweat there is, where its from, and its odour.

Muscles

Feminising hormones don’t in and of themselves reduce the size of existing muscles, but can make it more difficult to retain or increase existing muscle mass.

Hair

Feminising hormones cannot stop the growth of hair that already exists and has grown, but can prevent the growth of any additional hair over time, and slow male-pattern baldness.

Sex drive

Many people report a reduction in sex drive on feminising hormones, from a slight change to a complete end to sexual interest. If this is unwanted, this can be shifted by adjusting existing hormones, or adding a slight amount of testosterone to the mix, and you can talk to your doctor about how this might work for you.

Voice

Estrogen therapy by itself cannot affect the vocal chords, or raise the pitch of your voice. Vocal therapy and practice have a stronger effect on your voice. Some people also opt for vocal surgery.

Mood and mental health

Many people find that their mood on feminising hormones is calmer, and that their mental health becomes a lot easier to manage. For some people this is due to the euphoria experienced from starting hormones, for others it’s just a general sense of calm and better mental health.

This doesn’t mean that trans and gender diverse people on hormonal therapy don’t still experience mental health issues and require support for them, and there’s nothing wrong with needing help. For more information, check out our mental health page.

Fertility

Accounts vary on how feminising hormones affect fertility short and long term. It has long been held that estrogen therapy can and eventually will cause infertility.

However, there have been many anecdotal accounts of PMAB people stopping hormones for a period of time and successfully conceiving. Whether to hope this will be possible for you is a choice that each person will have to make for themselves.

For more information about fertility options, visit our page on fertility.

Accessing hormones in NSW

To assist you in connecting with your doctor, we’ve prepared a number of templates you can print, complete and take with you. Below you will find a template to let an existing or new doctor know that you want to start or continue hormones, and to update your name, gender marker and pronoun, if required.

We’ve also included an example of an informed consent form for initiating feminising hormones, as well as a GP Management Plan template. Your doctor may have a similar forms of their own, or you can print these out to work through together.

You are able to access hormones from your regular GP or Sexual Health Doctor. Hormonal affirmation and advice is not a specialist field, and does not require an expensive or difficult process, or access to a specialist to prescribe.

If you are over 18, you do not have to see a psychologist or psychiatrist in order to access hormones, unless you want to or your doctor feels it would be helpful.

For a list of doctors who support and understand trans people and our needs, check out ACON’s Gender Affirming Doctor List, available here.

Under 18s

For trans or gender diverse people under 18, gender affirming treatment can be commenced when there is no dispute between parents (or those with parental responsibility), the medical practitioner and the young person themselves with regard to:

The Gillick competence of an adolescent; or

A diagnosis of gender dysphoria; or

Proposed treatment for gender dysphoria

Any dispute requires a mandatory application to the Family Court of Australia as per the judgement of Re Imogen 2020.

The Standards of Care state that the following 3 criteria must be met for a person under 18 seeking medical gender affirmation:

A diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria in Adolescence, made by a mental health clinician with expertise in child and adolescent development, psychopathology and experience with children and adolescents with gender dysphoria.

Medical assessment including fertility preservation counselling has been completed by a general practitioner, paediatrician, adolescent physician or endocrinologist. This assessment should include further fertility preservation counselling by a gynaecologist and/or andrologist as required with referral for fertility preservation when requested.

The treating team should agree that commencement of estrogen or testosterone is in the best interest of the adolescent and informed consent from the adolescent has been obtained.

For more information about your legal and medical rights while under 18, go to our Under 18s page.

Downloads

Doctor letter: starting hormones - TransHub

Doctor letter: continuing hormones - TransHub

Informed consent: Feminising hormones - Dr Michelle Guttman-Jones

GP Management Plan: Feminising hormones - TransHub & Dr Holly Inglis

10 trans questions to ask a doctor - TransHub [ Plaintext version ]

10 tips for clinicians working with trans & gender diverse people - TransHub [ Plaintext version ]

Surgical readiness referral - TransHub

Gender affirming intake form for doctors - TransHub

Links

1 Position statement on the hormonal management of adult TGD individuals - Ada S Cheung, Katie Wynne, Jaco Erasmus, Sally Murray and Jeffrey D Zajac

2 Progesterone Is Important for Transgender Women’s Therapy—Applying Evidence for the Benefits of Progesterone in Ciswomen - Jerilynn C Prior

3 A Guide To Transgender Health - Rachel Heath and Katie Wynne

4 Family Court of Australia clears the way for young trans people to access hormone treatment without court authorisation - Human Rights Law Centre

5 Australian Standards of Care and Treatment Guidelines for Trans and Gender Diverse Children and Adolescents v1.1 [PDF] - The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne

Re: Imogen (No. 6) (2020) FamCA 761 (10 September 2020). - Family Court of Australia judgement

WPATH Standards of Care V7 [PDF]

Protocols for the Initiation of Hormone Therapy for Trans and Gender Diverse Patients [PDF] - Equinox Gender Diverse Health Centre, Thorne Harbour Health

Protocols for the provision of hormone therapy [PDF] - Callen Lorde, NY

Overview of feminizing hormone therapy - Madeline B. Deutsch

Trans children and medical treatment: the law [PDF] - Inner City Legal Centre

Prescribing for transgender patients - Louise Tomlins

Estrogen implant interview with Lara and Dr Darren Russell - The Cairns Sexual Health Service

Estrogen implant procedure, with Dr Darren Russell - The Cairns Sexual Health Service